ALIGN: A Frame for EdTech Integration Strategy

Why Strategic Intentions Keep Failing to Reach Operational Reality

[Updated December 2024 for accessibility based on feedback courtesy of Al Kingsley MBE, CEO of NetSupport and former BESA Edtech Group Chair. Frame and content unchanged; language made more accessible to improve readability]

What This Frame Is NOT (And Why That Matters)

Before we go any further, let’s establish what you won’t find here.

ALIGN is not:

A step-by-step implementation checklist

A simple solution to complex problems

Another technology recommendation list

A quick fix for educational technology strategy

Prescriptive instructions for teachers

An evaluation rubric for technology integration

If that’s what you’re looking for, this isn’t it. Close this tab. I won’t be offended.

However, if you’re exhausted by models that promise transformation through compliance, if you’ve watched procurement-first thinking fail repeatedly, if you know your institution is complex and resent being sold simplistic solutions, then what follows might resonate.

ALIGN is a way to structure strategic thinking and classroom practice using multiple frameworks, informing decisions without prescribing implementation.

It’s an integration of established research frameworks, each with distinct purpose.

It utilises professional judgment while working towards shared goals - autonomy, not compliance.

It provides clear structures for connecting strategic decisions to operational reality.

It’s designed to evolve, not remain static.

If that sounds more interesting than another implementation checklist, keep reading.

N.B. There is a reference list at the end of the article.

---

Building ALIGN as GenAI Hit Education

I’ve spent the past year developing ALIGN, a diagnostic frame for educational technology strategy.

The work draws on decades of documented research into why edtech initiatives systematically fail. Not incrementally failing. Systematically failing. The same mistakes, different technology, different decade.

My background spans management and education. I’ve worked across both sectors long enough to recognise these patterns. When I wrote Part 1 of this series, I diagnosed these failures, all documented in research:

Procurement-first thinking: Acquire tools, then figure out pedagogy.

Cultural dissonance: Technology culture meets education culture like matter meets antimatter.

Compliance-driven implementation: Top-down directives replace professional judgment.

Fragmented leadership: Strategic thinking disconnected from operational reality.

Confusing strategic/operational processes: Using classroom tools to make institutional decisions, for example.

I wasn’t responding to a specific technology. I was addressing 50+ years of persistent strategic failures across every wave of educational technology adoption, patterns that repeat whether the tool is an interactive whiteboard, an iPad, or artificial intelligence.

The ALIGN frame integrates established research into a way of thinking that tackles the root causes rather than symptoms.

Then, as I was building ALIGN, generative AI exploded into mainstream education.

Not the quiet ChatGPT launch in late 2022 that stayed relatively niche for educational institutions. The late 2024 and early 2025 explosion when ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini together made AI accessible, powerful, and impossible to ignore. Suddenly every school was grappling with the most powerful educational technology they’d ever encountered.

I watched, in real-time, as schools made identical strategic mistakes.

The “we need to buy more new tech!” reflex didn’t weaken. It intensified. “We must adopt AI!” became the new “We must have iPads!”. Leadership fragmented between enthusiasts insisting on adoption, skeptics resisting change, and others trying to find a middle ground. The middle ground it time to look at the new tech, decide how to integrate it, and only changing once a proven advantage is in place - due diligence as an educational leader.

The execution gap didn’t close. It widened.

The need for better ways to think strategically didn’t diminish. It became essential, rather than merely important. GenAI didn’t make ALIGN obsolete. It validated why the frame was necessary and made it urgent.

Schools now have unprecedented technological power and the same broken strategic thinking that’s failed for five decades. The stakes are just higher.

This isn’t about me, or about ALIGN, really. It’s about what’s systematically broken in how we think about educational technology, and more importantly, about what education fundamentally is that makes broken strategy so damaging.

Tyack & Tobin’s (1994) research on the ‘grammar of schooling’ showed why reform efforts persistently fail; they attempt to add new practices to unchanged institutional structures. Technology initiatives are no exception; simply adding tools to existing organisational patterns doesn’t transform practice, it gets absorbed or rejected. ALIGN addresses institutional patterns themselves by examining them from multiple angles rather than assuming technology additions will drive change.

Understanding the Execution Gap

Two educators recently articulated what many practitioners are familiar with - the systematic failure between strategic intention and operational reality.

The execution gap occurs when strategic decisions don’t translate to operational practice. Policies exist but aren’t followed. Teachers are trained but don’t implement. Tools are provided but drift into misuse. Not through defiance or incompetence, but simply because the systems connecting what leaders plan to what actually happens don’t work as intended.

When the known, and shared, strategy is absent or fails to translate, organsations can end up on autopilot, with the operational level just continuing as before, and ignoring the strategy. The “grammar of schooling”, those persistent patterns Tyack & Tobin documented, fills the vacuum - how time is organised, how learning is assessed, how authority flows, how classrooms are structured. These patterns have remained remarkably stable across a century despite repeated reform attempts. Not deliberately chosen, not consciously implemented, but functioning as the actual strategy nonetheless, to quote Adam Boxer “do what the immediate context supports, abandon what it doesn’t.” This is autopilot mode.

Adam Boxer’s “Getting Worse at Teaching” shows this gap at individual level. A teacher trained in evidence-based practices loses those skills when changing schools because the new environment provides no infrastructure to sustain them e.g. the school have a strategy supporting the adoption of evidence-based practices. The default pattern reasserts itself.

His “Autonomy, Authority and Anarchy” reveals the gap at institutional level. Schools have policies (officially: “we use Cold Call”) but different practices (reality: students call out). Not deliberate non-compliance, just gradual decay when the chosen strategy lacks operational support, possibly due to a communication gap.

David Didau’s “Promise and Price of Autonomy” explains a critical dimension, that granting teacher autonomy before competence develops doesn’t produce innovation, it produces drift. Autonomy without the necessary skills, the prerequisites, becomes a burden, forcing professionals to make judgments they’re not equipped to make well, with students bearing the consequences. As Didau makes it clear, autonomy must be earned through demonstrated competence, not granted prematurely as permission; autonomy is not a right.

I developed ALIGN from observing this execution gap persistently across organisations. I couldn’t frame it as eloquently as Boxer and Didau have, but I could see its existence and the damage it caused. Their recent diagnostic precision validates what I was attempting to address; many schools operate on autopilot but simply because the systems connecting what leaders plan to what actually happens don’t work as intended.

ALIGN offers that system. Not as THE solution, but as A structured approach specifically designed to replace “doing nothing and hoping for the best” with deliberate planning. It uses two connected levels; a strategic level for looking honestly at how the institution works, and a practical level for what happens in classrooms. Between those sit the connecting pathways (Panakaje et al., 2024) that link strategy to daily practice - the missing join in most schools. The five phases build people up over time by providing clear structure and support at the start, then gradually increasing teachers’ freedom as their confidence and skills grow.

---

ALIGN’s Structure: Overview

More detail follows after the “Why Technology Integration Keeps Failing (The 50-Year Pattern)”, “Why This Matters More Than Implementation Fidelity” and “The Research Evidence (Why This Isn’t Just Opinion)” sections, in How ALIGN Works (The Architecture).

ALIGN architecture operates through five phases:

Assess: Honest assessment of where you are at both levels, the baseline diagnosis.

Link: Connect operational intent to strategic vision.

Integrate: Build infrastructure, embed practice.

Gauge: Evaluate outcomes vs objectives - gaps constitute learning opportunities, not failures.

Nurture: Sustain through culture, distributed leadership, decision-making and responsibility, leading to earned autonomy

This is about understanding and diagnosing, not a step-by-step checklist. ALIGN helps people think from multiple perspectives without replacing professional judgment. It’s complex but not complicated; its multiple interconnected frameworks match the complex systems it’s designed to navigate, with transparent logic and learnable structure.

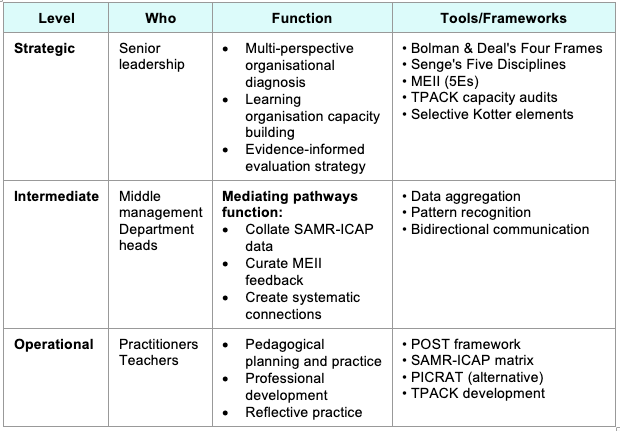

ALIGN provides a diagnostic process addressing the execution gap through three connected levels:

Strategic Level, ALIGN, equips institutional leadership with:

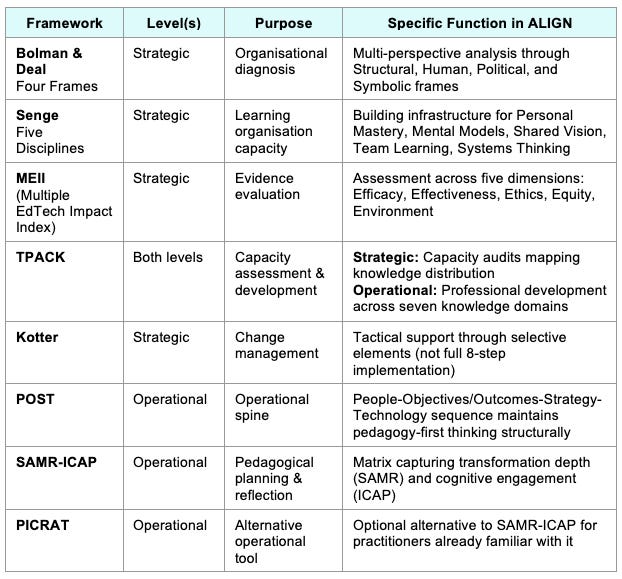

Bolman & Deal’s Four Frames for multi-perspective organisational diagnosis. (Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2017).

Senge’s Five Disciplines for learning organisation capacity. (Senge, P. M. 1990/1994 and Senge, P.M. et al. 2012).

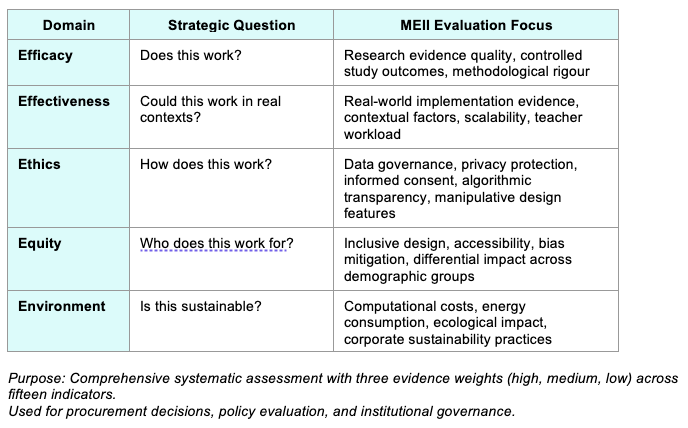

MEII (Multiple EdTech Impact Index) for evidence evaluation across five dimensions: Efficacy, Effectiveness, Ethics, Equity, Environment. (Kucirkova, N., Uppstad, P. H., Holeton, R., Irwin, J., & Rosen, D. 2025)

TPACK capacity audits mapping knowledge distribution. (Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. 2006).

Selective Kotter change management elements. (Kotter, J. P. 1996).

Operational Level (ALIGN-ops) provides practitioners with:

POST framework, adapted from Li & Bernoff’s Groundswell (2008), sequencing People-Objectives+Outcomes-Strategy-Technology to maintain pedagogy-first thinking structurally, not aspirationally.

SAMR-ICAP for pedagogical planning and reflection on technology’s transformative depth and cognitive engagement. (Puentedura, R. R. 2006 and Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. 2014).

PICRAT as an alternative operational planning and reflection tool. (Kimmons, R., et al. 2020).

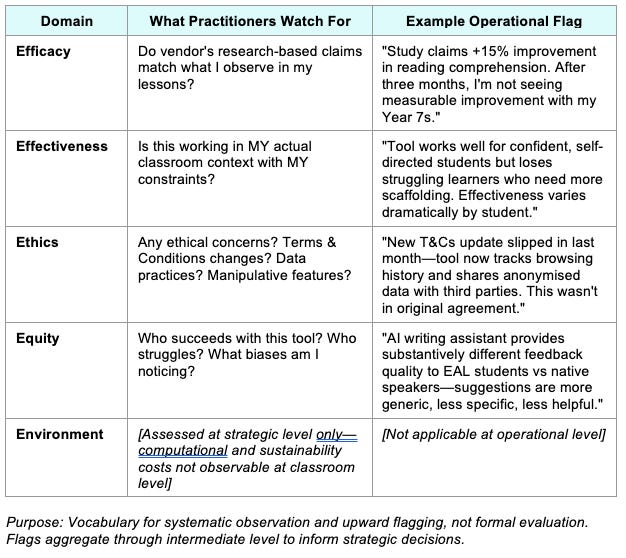

The 5E’s from MEII as a sentinel function to track how technology matches up to vendor claims over the five dimensions of Efficacy, Effectiveness, Equity, Ethics and Environment. (Kucirkova, N., Uppstad, P. H., Holeton, R., Irwin, J., & Rosen, D. 2025)

Intermediate Level:

Middle management/department heads provide the connecting pathways function (Panakaje et al. 2024).

Collating and curating SAMR-ICAP pedagogical reflection data and MEII feedback from operational level using the 5E’s of EdTech Impact from MEII (Kucirkova, N. 2023).

Creating systematic connections between strategic decisions and operational reality.

---

Why Technology Integration Keeps Failing (The 50-Year Pattern)

Here’s the pattern that repeats with the launch of every new technology:

Technology-first adoption.

Organisation acquires tools. Driven by marketing. Driven by trends. Driven by enthusiasm. Sometimes driven by genuine belief in transformation.

Then pedagogy adapts to use the tools.

The consequence is technology-led practice where tools drive educational change rather than serving educational purposes. Not education driven by pedagogy.

I discussed the full extent, historically and globally in Why EdTech Strategy Keeps Failing – A Structural Diagnosis (Part 1).

Børte & Lillejord’s 2024 research proves that this approach is backwards.

Their design-based research shows successful integration demands “educational purpose as constant guide” from the very beginning. Not “technology selection first, pedagogy later”. Pedagogy must lead technology throughout. We need to create PedTech, from edtech.

Yet the sector systematically violates this principle. Why? Because strategic and operational thinking get merged and confused, i.e. conflated. This is the core execution gap.

Senior leaders use classroom-level tools (e.g. SAMR’s four-level hierarchy) to make institutional decisions about technology strategy. They see “teachers mostly at substitution level” and instruct them to “move toward transformation.”

That’s the problem. SAMR was designed for individual teacher planning and reflection, not strategic institutional decisions.

Meanwhile, practitioners may receive strategic frameworks (complex change management models) for lesson planning. They’re told to “align with institutional strategy” using tools designed for organisational systems thinking.

That’s the same problem, just the other way around! Strategic frameworks overwhelm operational decisions.

Unsurprisingly, neither works.

Let’s be precise about the distinction:

Strategic thinking involves:

Multi-perspective organisational diagnosis.

Systems-level pattern recognition.

Long-term consequence analysis.

Coordinating across units and departments.

Resource allocation decisions.

Evidence interpretation at institutional scale.

Operational practice involves:

Classroom-level pedagogical decisions.

Lesson design for specific students.

Immediate instructional choices.

Professional judgment in real-time.

Adaptation to emerging needs.

Evidence of learning with these students.

They’re both essential.

They’re both sophisticated.

They’re fundamentally different in scope, scale, and temporal frame.

When we conflate them:

Strategic decisions get made without diagnostic depth. Leaders see “low technology use” without understanding barriers exist in infrastructure (Structural Frame), support structures (Human Frame), decision-making processes (Political Frame), or cultural narratives (Symbolic Frame).

Operational practice gets overwhelmed with inappropriate complexity. Teachers receive strategic directives without operational scaffolding showing how to translate strategic direction into classroom practice.

Technology gets purchased before pedagogical purposes are established. Procurement-first thinking emerges because no diagnostic process asks “what pedagogical problems require solving?” before “what tools should we buy?”

Teachers receive mandates without infrastructure support. Strategic intent (”increase collaborative learning”) disconnects from operational reality (”I have 32 students, 18 laptops, and unreliable wifi”).

Evidence gets ignored because we’re measuring wrong things. We count technology usage (output) rather than examining learning outcomes. We measure compliance rather than understanding.

This is what ALIGN addresses. Not through new methodology to implement. Not through another framework requiring fidelity monitoring.

Through diagnostic thinking that:

Works with complexity rather than either ignoring, or pretending it doesn’t exist.

Works with professional judgment rather than replacing it with procedures.

Maintains pedagogical purpose whilst navigating the organisational reality.

Creates clear connections between strategic decisions and operational practice

---

Why This Matters More Than Sticking to a Plan

Now that you’ve seen ALIGN’s structure, and the events leading to its development, let’s examine the philosophical principles that necessitate this specific design.

Schools Are Complex Adaptive Systems (It’s Not Just Academic Jargon)

Education isn’t merely complicated, like a machine. It’s complex.

Full of nuance. Context. Relationships. Humans. Social media has trained us to prefer simplicity, polarised viewpoints requiring no thought, problems with single causes, solutions that fit in tweets. Anyone who’s actually spent time in education knows the truth - schools are living ecosystems.

The formal term is Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS). In education this means, teachers, students, parents, leadership, and the environment within a school, are all constantly interacting and influencing each other. Results emerge from all those connections - you can’t predict outcomes the way you can predict how a machine will work, because people aren’t cogs. The same approach that transforms one school might fail completely in another, not because someone ‘implemented it wrong’ but because the people, relationships, and context are genuinely different.

This is why top-down strategies fail.

This is why prescriptive compliance methods break against classroom reality.

This is why “what works” research often doesn’t work when you try to replicate it.

The fundamental mismatch is treating complex systems as if they were merely complicated. As if education were machinery requiring the right manual rather than an ecosystem requiring navigation. (Ahmad, M. A., et al. 2024 and Keshavarz, N., et al. 2010).

Here’s where it gets interesting.

Technology culture embraces what Peter Senge (1994) calls reinforcing loops; amplification, acceleration, disruption, all popularised as “move fast and break things.” Silicon Valley worships rapid growth, innovation and constant disruption.

Education culture embraces what Senge calls balancing loops: stability, safeguarding, consistency, as with medicine, the credo of “first, do no harm.” Schools safeguard children. They provide stability in chaotic lives. They move deliberately because the cost of breaking things is measured in young lives.

Both are necessary for healthy systems. Reinforcing loops enable growth. Balancing loops provide stability. When they collide without arbitration? You get what I call a cyclonic cauldron, a “perfect storm” where schools get battered by contradictory forces. Often lacking a sea-anchor, the stability offered by strategy, which maintains pedagogical direction and control whilst still adopting technology. School leaders are stretched on a rack between “innovate or die” and “protect at all costs.”

No wonder strategy fails.

Teachers Are Professionals, Not Implementers

What gets lost when experts treat educational technology as a technical problem is that the system forgets that teachers often have sophisticated judgment developed through years of practice.

Teachers are not technicians executing prescribed procedures. They’re not “resources” to be managed like equipment. They’re not resistors of change requiring “buy-in strategies.”

They’re professionals. They need to be kept informed and be part of the decision process.

When we hand them frameworks and expect compliance, we disrespect the fundamental nature of educational work.

ALIGN operates from a different premise, that of professional trust, not compliance against ever more metrics. Teachers possess distributed expertise throughout the institutional hierarchy that strategic leaders need.

Their current classroom reality.

Their current knowledge of students as humans, not data points.

Their pedagogical judgment honed through countless hours of hours of current practice.

These aren’t obstacles to strategy. They’re essential experience providing data for strategic thinking. The challenge isn’t getting teachers to comply with decisions made in conference rooms. The challenge is creating conditions where their professional judgment informs those decisions in the first place, and where they have autonomy clear common and shared goals.

Not compliance. Not autonomy without direction. Autonomy with shared understanding and goals.

That’s harder. Much harder. It requires genuine dialogue, not consultation theatre. It requires leaders who can maintain strategic direction whilst distributing decision-making. It requires clear structures that connect strategic and operational levels without mixing them up.

Which brings us to...

Outcomes, Not Outputs

Education obsesses over outputs; lesson plans delivered, technologies deployed, policies implemented, professional development sessions attended, measured adherence to the plan, no deviation.

Which is a shame, as what actually matters, are outcomes.

What happens with students. What they learn. How they develop. Whether they flourish or merely comply. This distinction isn’t semantic wordplay.

When we focus on outputs, we measure compliance. Did teachers use the technology? Check. Did students complete the assignment? Check. Did we roll out the initiative as planned? Check.

When we focus on outcomes, we examine reality. Did students actually learn? Did understanding deepen? Did capability increase? Did technology serve pedagogical purposes or was it performative compliance?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth; outcomes often don’t map to planned objectives.

You plan “students will develop critical thinking through collaborative inquiry” and discover they’re actually learning “how to appear collaborative whilst doing minimal cognitive work.”

That gap, between what you intended and what actually occurred, is where learning happens, by analysing that gap between Objective and Outcome.

Not shame. Not failure. Learning.

Understanding what didn’t work and why, so practice can evolve. Gap analysis.

This requires Reflect-Reframe-Realign as a continuous practice, not as special “reflection activities” scheduled quarterly:

Reflect: Examine evidence honestly. What’s actually happening, not what I wish were happening?

Reframe: Shift understanding based on learning. What does this evidence mean about my assumptions?

Realign: Adjust practice accordingly. How does this change what I do next?

This operates continuously. It’s an operational mindset, not a calendar event. It’s how you honour complexity whilst maintaining purposeful action.

Thought and Dialogue Over Compliance (Why Real Conversation Matters)

ALIGN embraces dialogue for both strategic thinking and operational practice. Not just “conversations.” Not consensus-seeking. Not consultation theatre, where decisions are already made and staff feedback is simply box-ticking. Real conversation where people are encouraged to challenge each other’s thinking! Think “Harkness Method”, but for teachers.

Strategic leaders talk through their thinking out loud, examining them from multiple angles. Making space for different viewpoints, where assumptions get questioned, where people explain their thinking and improve it through discussion. The conversations could include the mid-level people. They carry out the same process with the classroom teachers. This way strategy information makes it’s way to the practitioner level, and feedback about the reality of the classroom informs strategy.

The goal isn’t consensus. It’s understanding. It’s making thinking visible so it can be examined, challenged, refined.

Failure as Learning, Not Shame (The Recursion Principle)

In complexity, re-visting earlier stages, recursion, isn’t failure.

It’s adaptive intelligence.

Returning to earlier phases when evidence demands it demonstrates strategic maturity, not planning inadequacy. The capacity to say “this isn’t working as intended, let’s diagnose why and adjust” is precisely what complex systems require.

What really happens, too often:

Every adjustment gets labelled “it didn’t work.”

Every change of direction becomes evidence of poor leadership.

Every return to assessment phase gets interpreted as “we didn’t think this through initially.”

This creates cultures where people hide problems instead of examining them.

Where “staying the course” becomes virtue even it turns you into a lemming and leads you off a cliff.

Where admitting “we got this wrong” feels like professional suicide.

When schools treat adjustment as failure, they eliminate their capacity to learn.

When they treat adjustment as learning, they create conditions for genuine improvement.

ALIGN isn’t linear. Recursion can occur from any phase, though Gauge, as the natural review point before embedding during the Nurture phase, invites it most obviously.

As ALIGN embeds, something more interesting should emerge; people develop habits of continuous review.

Not ‘what’s broken?’ but ‘can we improve this effectively?’

Brief dialogues about what happened v. what was planned.

Cost-benefit thinking.

Professionals who’ve regained ownership start questioning and adapting without waiting for permission.

The design of ALIGN enables this, and spreading responsibility cultivates it. Whether it actually emerges that way? Field testing will reveal. In theory, though, this is how professional judgment returns and learning organisations function.

ALIGN’s recursive structure, Assess → Link → Integrate → Gauge → Nurture, and repeat, isn’t weakness. It’s design. Recursion can occur from any phase, back to any previous phase. Which phase to return to depends on when an error comes to light, and the origin of the error.

Organisations don’t implement ALIGN once and finish. They cycle through it as contexts change, as technology evolves, as understanding deepens. Eventually it becomes embedded as a new philosophy and culture; it’s simply the way the school does things.

That’s not failure. That’s how Learning Organisations function (Senge, P. M. 1990/1994 and Senge, P.M. et al. 2012).

---

The Research Evidence (Why This Isn’t Just Opinion)

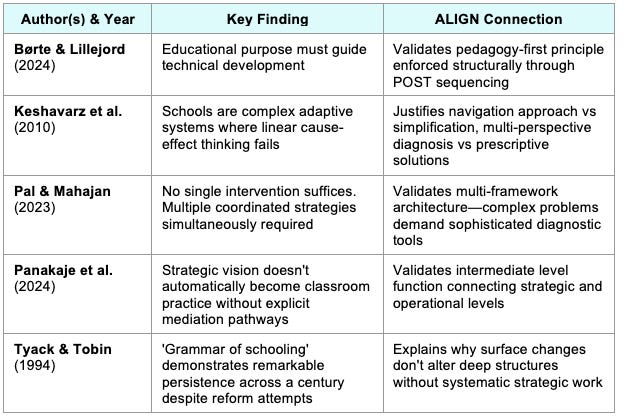

So, we’ve covered the historical precedents that led to ALIGN’s development , looked at its basic structure, considered its underlying philosophy, so now let’s review the research that supports the design intent and structure of ALIGN.

This isn’t speculation. Decades of research document these persistent patterns. There is a full list of research at the end of this article.

Børte & Lillejord’s 2024 research on learning design tools demonstrates that educational purpose must guide technical development, not adapt to it. Their interdisciplinary team’s continuous alignment process, maintaining pedagogical intent throughout design, validates ALIGN’s structural principle: pedagogy leads, technology follows, is actually built-in, not just stated as a goal.

Costa, Hammond & Younie (2019) identify six shortcomings that keep appearing in educational technology research and practice:

Technological determinism (assuming technology inherently transforms learning).

Binary categorisations (adopters vs resisters, digital natives vs immigrants).

Naive romanticism about technology’s transformative power.

Describing without analysing.

Unexamined power dynamics.

Not thinking deeply enough about technology itself.

Keshavarz, Nutbeam & Rowling (2010) establish schools as complex adaptive systems where simple cause-effect thinking fails. Technology adoption creates unexpected reactions. Unpredictable interactions. What works brilliantly in one context fails in another not because implementation was poor but because contexts are genuinely different. Single-frame thinking (usually Structural: “we need better policies”) misses crucial dynamics in other frames.

Pal & Mahajan’s 2023 systematic review of technology integration in teacher education confirms no single intervention works. Multiple coordinated strategies are required simultaneously - teacher learning, institutional support, pedagogical approaches, and technological infrastructure. This validates ALIGN’s multi-framework integration as complex problems require sophisticated ways of dealing with complex issues, not simplified solutions.

Panakaje et al. (2024) demonstrate that strategic vision doesn’t automatically become classroom practice without clear connecting pathways. Most organisational change initiatives fail when trying to translate strategy into practice. Strategic intent doesn’t transform into operational reality through directives, wishful thinking or “communications strategies.” It requires a structure in place specifically to share and modify information, enabling successful transfer between operational and strategic levels.

Schmitz et al. (2023) show that transformational leadership affects technology integration through enabling conditions such as infrastructure, professional development, capacity-building and not through direct classroom intervention. Strategic leaders who attempt to mandate specific technology uses (e.g., “all teachers will use interactive whiteboards for collaborative learning”) bypass the actual mechanisms of effective change. They confuse strategic direction-setting with operational prescription.

Tyack & Tobin’s 1994 “grammar of schooling” demonstrates the remarkable persistence of educational structures across a century despite repeated reform attempts. Technology integration fails not from teacher resistance or inadequate tools but from underestimating how deeply institutional patterns are embedded (which might seem like teacher resistance!). Surface changes (new devices) don’t alter deep structures (how time is organised, how learning is assessed, how authority flows) without systematic strategic work addressing why those structures persist.

This research converges, demonstrating that technology integration requires sophisticated diagnostic thinking that addresses systemic causes, respects complexity, honours professional judgment, and maintains pedagogical purpose.

Exactly what ALIGN provides.

---

How ALIGN Works (The Architecture)

Historical precedent, basic structure, underlying philosophy, validating and underpinning research have all be discussed. Now, to the core of ALIGN.

ALIGN stands for: Assess, Link, Integrate, Gauge, Nurture.

Five phases that organisations cycle through recursively as contexts change. The innovation isn’t five phases. After all, plenty of frameworks have phases.

The innovation is dual-level architecture with clear connection between strategy and operations, but with clear lines between their roles.

The ALIGN frame integrates eight established models:

1. Bolman & Deal: organisational diagnosis.(Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. 2017).

2. Senge: Learning Organisation capacity.(Senge, P. M. 1990/1994 and Senge, P.M. et al. 2012).

3. MEII (Multiple EdTech Impact Index): evidence evaluation. (Kucirkova, N., Uppstad, P. H., Holeton, R., Irwin, J., & Rosen, D. 2025).

4. TPACK: capacity assessment and development. (Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. 2006).

5. Kotter: tactical change support (selective elements). (Kotter, J. P. 1996).

6. POST: operational thinking structure. (Li, C., & Bernoff, J. 2008).

7. SAMR-ICAP: pedagogical planning and reflection. (Puentedura, R. R. 2006 and Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. 2014)

8. PICRAT: alternative operational tool for planning and reflection. (Kimmons, R., Graham, C. R., & West, R. E. 2020)

This is diagnostic, not prescriptive.

ALIGN doesn’t provide implementation checklists or step-by-step instructions. It structures strategic thinking and operational practice, enabling sophisticated professional judgment rather than replacing it with compliance procedures.

ALIGN is complex but not complicated. Complex systems, like schools, require complex diagnostic tools. Complexity doesn’t mean confusion. ALIGN’s multi-framework integration mirrors the interconnected nature of what it diagnoses. Its logic is transparent, its structure is learnable, its diagnostic questions are straightforward. We’re not simplifying complexity away, we’re providing scaffolding to navigate it intelligently.

Strategic ALIGN (for senior leadership):

Multi-frame diagnostic thinking using Bolman & Deal’s Four Frames:

Structural perspective: goals, roles, policies, coordination mechanisms.

Human perspective: people’s needs, development, relationships.

Political perspective: power, coalitions, conflicts, resource competition.

Symbolic perspective: culture, meaning, narrative, ritual.

Every strategic question examined through all four frames. Not favouring one of them unconsciously.

Learning organisation capacity through Senge’s Five Disciplines:

Personal Mastery: individual professional development.

Mental Models: examining assumptions, surfacing beliefs.

Shared Vision: collective purpose genuinely owned.

Team Learning: dialogue, collective inquiry.

Systems Thinking: interconnections, feedback loops, unintended consequences.

These aren’t sequential steps. They’re ongoing practices building institutional capacity to learn; that is, the ability of the people within an organisation to learn together, to develop a shared philosophy, culture and understanding, increasing their ability to work coherently.

Evidence-informed strategy using MEII (Multiple EdTech Impact Index):

Efficacy: Does it work under ideal conditions?

Effectiveness: Does it work in real-world contexts?

Ethics: Does it respect privacy, autonomy, wellbeing?

Equity: Does it reduce or reinforce existing inequalities?

Environment: What are ecological costs? What systems required?

Not just “does it work?” but impact across five dimensions. Technology may work pedagogically whilst creating privacy violations. May improve efficiency whilst reinforcing inequality.

ALIGN-ops (for practitioners):

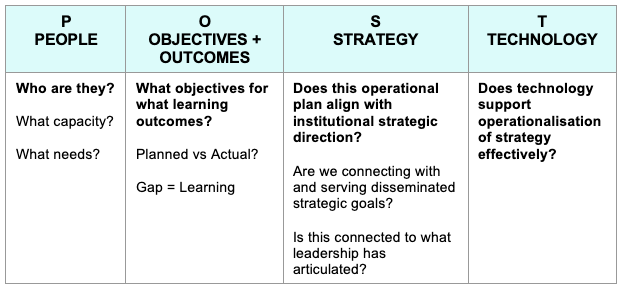

POST operational framework: People → Objectives → Strategy → Technology

Sequence matters. Technology comes LAST, not first.

ALIGN-ops uses the POST framework as its operational spine (adapted from Li & Bernoff’s Groundswell, 2008) running through all five phases. POST structurally enforces pedagogy-first thinking. You can’t consider technology until you’ve clarified:

People: capacity and readiness to learn, not just tool knowledge.

Objectives/Outcomes: critical distinction between planned (objectives) and actual (outcomes); the gaps between them constitute learning opportunities, not failures.

Strategic alignment: checking whether operational planning aligns with disseminated strategic direction as part of Panakaje et al’s mediating pathways function, thus mitigating execution gaps.

Technology: retains Groundswell’s tech-agnosticism ensuring that tools serve pedagogical purposes, not drive them.

POST maintains pedagogy-first principle as a structural design-feature, not simply because it’s envisioned. If technology doesn’t support the pedagogical strategy, don’t use it. Technology serves pedagogy, not the reverse, hence we aim to achieve PedTech (pedagogy-first technology) rather than the vague catch-all which is edtech. Therefore, technology has to be the FINAL consideration.

SAMR-ICAP Matrix for planning and reflection:

This combines two dimensions that both matter:

SAMR (task redesign): Substitution → Augmentation → Modification → Redefinition

ICAP (cognitive engagement): Passive → Active → Constructive → Interactive

Why both? Because Schmitz et al. (2023) prove that measuring technology frequency alone misses quality. We have two excellent models, that both have gaps, but both have useful dimensions that provide useable feedback.

You can have sophisticated technology enabling passive learning (Redefinition-Passive: VR historical immersion where students passively experience).

You can have simple technology supporting high cognitive demand (Substitution-Interactive: collaborative annotation on digital text).

Both dimensions matter. Neither determines the other. The 4×4 matrix (16 cells) captures this.

Teachers code lessons during planning: “I’m aiming for Augmentation-Constructive.” Post-lesson reflection: “Actually delivered Substitution-Active—why? What assumptions broke down?”

5Es (from MEII) Operational Sentinel Function

Strategic MEII evaluation occurs before procurement and periodically thereafter which means that practitioners don’t conduct formal MEII evaluations. In ALIGN-ops the 5Es (Kucirkova, N. 2023) act as sentinels, an aide-memoire to provide continuous monitoring during actual use. Essentially, this process provides a reality-check of vendor claims and flags concerns by using the simplified 5Es as prompts if they observe something untoward. Both inform institutional intelligence, MEII at a strategic level, the 5E’s at operational level. Neither replaces the other, both offer valuable data to exchange through the mid-level, that informs everyone.

There isn’t evaluation expertise required. It’s vocabulary for systematic tracking of what was promised, against what the technology delivers.

“This information the tech is asking for makes me uncomfortable” becomes “Ethics flag: new data collection without clear purpose.”

Individual flags aggregate through middle management. Patterns inform strategic decisions. It’s an early warning system for effectiveness (against efficacy), ethical and equity concerns before they become institutional crises.

This is particularly critical with GenAI proliferation:

Teachers notice AI writing assistant gives weaker feedback to EAL students (Equity)

A tool introduces personality profiling without consent (Ethics)

Effectiveness claims don’t match classroom reality (Efficacy/Effectiveness gap).

These operational sentinels enable proactive governance, not reactive crisis management.

TPACK professional development:

Seven knowledge domains developed systematically, not assumed to exist:

Content Knowledge (subject expertise).

Pedagogical Knowledge (teaching methods).

Technological Knowledge (understanding tools).

Plus four integration domains where these intersect.

Teachers develop capacity over time through purposeful CPD, not through directives. They also develop competence and understanding by planning and reflecting on lessons using SAMR-ICAP, by reflecting and acting on the difference between what was planned, and the actual outcome.

Connection Without Confusion:

Strategic team doesn’t use operational tools. Practitioners don’t navigate strategic complexity. This is part of the complexity. These two areas needs to connect, preferably through a clean and clear pathway.

Teachers code lessons (SAMR-ICAP). Department heads gather patterns. “Science department concentrated in Augmentation-Active region.” Strategic team receives this data with context.

Strategic decisions (e.g. resource allocation, professional development priorities) informed by operational reality. Operational practice (e.g. lesson design) occurs within current strategic direction.

Two-way exchange of data + an intermediary (mid-level) for context = Connection without confusion.

---

What Actually Changes in Practice

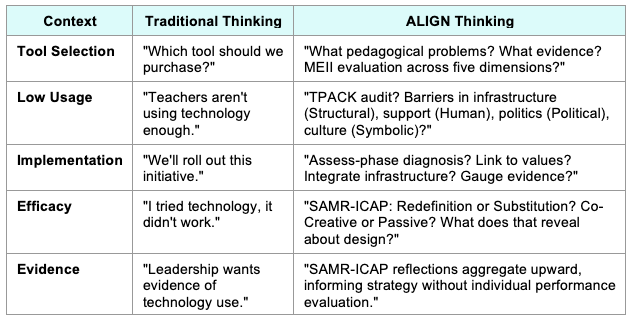

Some examples of what strategic thinking could look like through ALIGN’s lens:

Strategic Level:

Before: “Which tool should we purchase?”

ALIGN diagnostic: “What pedagogical problems require solving? What evidence suggests technology could address them? What would MEII evaluation reveal about candidate tools across Efficacy, Effectiveness, Ethics, Equity, and Environment?”

—

Before: “Teachers aren’t using technology enough.”

ALIGN diagnostic: “What does TPACK capacity audit reveal about knowledge distribution? Do barriers exist in infrastructure (Structural Frame), support structures (Human Frame), decision-making processes (Political Frame), or cultural narratives (Symbolic Frame)?”

—

Before: “We’ll roll out this initiative next term.”

ALIGN diagnostic: “What does Assess-phase diagnosis reveal about current state? Does Link-phase vision connect to institutional values? Has Integrate-phase work created necessary infrastructure? What will Gauge-phase evidence collection examine? Do we need pilot programmes first?”

Operational Level:

Before: “Use the iPads because we’ve got them.”

ALIGN-ops POST thinking: “What do these specific students need (People)? What are we trying to achieve pedagogically (Objectives)? What instructional approaches serve those purposes (Strategy)? Do iPads support that strategy effectively (Technology)? If yes, use them. If not, don’t.”

—

Before: “I tried technology, it didn’t work.”

ALIGN-ops reflection: “SAMR-ICAP: Did technology enable something previously impossible (Redefinition) or just replace traditional tool (Substitution)? Were students collaborating to create knowledge (Interactive) or passively receiving (Passive)? What does that reveal about my pedagogical design assumptions?”

—

Before: “Leadership wants evidence of technology use.”

ALIGN-ops: “My SAMR-ICAP reflections aggregate upward, informing institutional understanding without being used for individual performance evaluation. I maintain professional autonomy whilst contributing to strategic insight through voluntary self-reporting.”

See the pattern? ALIGN structures diagnostic thinking at both levels. This prevents technology-first reasoning. Maintains appropriate complexity for each function. Creates systematic feedback between strategic decisions and operational reality.

ALIGN doesn’t offer simplification. It offers navigation.

---

Where This Goes Next

This overview presents ALIGN’s foundational architecture:

Dual levels (strategic and operational).

Integrated frameworks (eight total, each with clear purpose).

Pedagogy-first enforcement (structurally, not aspirationally).

Research grounding (decades of established work).

Philosophical commitments (complexity, trust, dialogue, learning).

The comprehensive framework article provides complete detail:

Full phase-by-phase breakdowns (strategic and operational).

All framework integration mappings.

Theoretical foundations.

Implementation considerations.

ALIGN-ops deserves deeper exploration than this overview permits. The operational level warrants detailed examination:

How POST functions across all five phases with resource constraints.

How SAMR-ICAP planning connects to post-lesson reflection.

How middle management translation actually works.

How practitioners maintain autonomy whilst generating strategically useful data.

For those interested in theoretical foundations, the research synthesis explores:

Complexity theory grounding.

Full interconnections across cited studies.

Epistemological commitments underlying ALIGN’s design.

The questions ALIGN raises are larger than any single framework:

Can systematic integration of established research frameworks provide the diagnostic sophistication educational technology strategy currently lacks?

Is respecting complexity whilst maintaining strategic coherence possible?

Can we utilise professional judgment whilst building institutional capacity?

Is this the start of a re-design in education that people are talking about?

These questions matter regardless of whether ALIGN proves to be the answer.

The frame is offered as a contribution to the ongoing dialogue about how schools can navigate educational technology strategy coherently whilst respecting institutional complexity. It’s an invitation to collaborative exploration of whether systematic integration of established research frameworks can provide the diagnostic sophistication educational technology strategy currently lacks.

The conversation itself has value, possibly more so than a conclusion.

---

N.B. ALIGN is theoretical synthesis awaiting field validation.

Nothing about ALIGN is new, other than the thinking and the connections it makes to synthesise the donor models and theories into a functional whole.

It draws on decades of established research across organisational learning, change management, and educational technology. It hasn’t been empirically validated as a complete integrated framework because it’s new.

However, all the donor models stand on their own feet, primarily through research and latterly through utility and familiarity. The innovation of ALIGN is bringing them together and connecting them. Is the sum greater than the parts? At this juncture, I don’t know, but I do know that the parts themselves carry the necessary weight.

What I’m presenting here is diagnostic process and how it can structure thinking about technology integration. Implementation will test, refine, and potentially challenge these principles.

---

About the ALIGN series:

Part 1: Why EdTech Strategy Keeps Failing

Part 2: ALIGN Frame – From Vision to Execution (comprehensive article, forthcoming)

Supporting research and theoretical foundations (in development)

If you found this valuable, please share with colleagues facing similar strategic challenges. The more we discuss these systemic failures openly, the better our collective understanding becomes.

References/Bibliography

Ahmad, M. A., Baryannis, G., & Hill, R. (2024). Defining complex adaptive systems: An algorithmic approach. Journal of Systems Science and Complexity, 37(1), 1-23.

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2017). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (6th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Børte, K., & Lillejord, S. (2024). Learning to teach: Aligning pedagogy and technology in a learning design tool. Computers and Education Open, 6, 100175.

Boxer, A. (2024, November). Getting worse at teaching. Carousel.

Boxer, A. (2024, November). Autonomy, authority and anarchy: Creating the conditions for effective teaching. Carousel.

Cherner, T., & Mitchell, C. (2020). Deconstructing edtech frameworks based on their creators, features, and usefulness. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(4), 473-495.

Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219-243.

Costa, C., Hammond, M., & Younie, S. (2019). Theorising technology in education: An introduction. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 28(4), 395-399.

Didau, D. (2024, November). The promise and the price of autonomy. The Learning Spy.

Keshavarz, N., Nutbeam, D., & Rowling, L. (2010). Schools as social complex adaptive systems: A new way to understand the challenges of introducing the health promoting schools concept. Social Science & Medicine, 70(10), 1467-1474.

Kimmons, R., Graham, C. R., & West, R. E. (2020). The PICRAT model for technology integration in teacher preparation. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 20(1), 176-198.

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9(1), 60-70.

Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Harvard Business School Press.

Kucirkova, N. (2023). How can philanthropy catalyse a system-wide change in EdTech? Alliance magazine

Kucirkova, N. (2024). Outputs are not outcomes: Why evidence of impact matters in edtech. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72(3), 1245-1262.

Kucirkova, N., Cermakova, A. L., & Vackova, P. (2024). Consolidated benchmark for efficacy and effectiveness frameworks in edtech. University of Stavanger.

Kucirkova, N., Uppstad, P. H., Holeton, R., Lin, D., Clark-Wilson, A., & Chigeda, A. (2025). Evaluating educational technology: Consolidating across multiple impact indicators and rating systems. Computers & Education, 105467.

Li, C., & Bernoff, J. (2008). Groundswell: Winning in a world transformed by social technologies. Harvard Business Press.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge - A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054.

Pal, S., & Mahajan, R. D. (2023). Exploring effective strategies for integrating technology in teacher education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 51(3), 412-431.

Panakaje, N., Naik, P., & Jain, S. (2024). Strategic planning frameworks for technology integration in education: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Management, 38(2), 245-267.

Puentedura, R. R. (2006). Transformation, technology, and education. http://hippasus.com/resources/tte/

Rodgers, J. (2024). Embracing complexity: Why schools are complex adaptive systems. Research School Network. https://researchschool.org.uk

Schmitz, M. L., Antonietti, C., Consoli, T., Cattaneo, A., Gonon, P., & Petko, D. (2023). When barriers are not an issue: Tracing the relationship between hindering factors and technology use in secondary schools across Europe. Computers & Education, 201, 104819.

Senge, P. M. (1990/1994). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday.

Senge, P. M., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., & Dutton, J. (2012). Schools that learn: A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education (Updated and revised ed.). Crown Business.

Tyack, D., & Tobin, W. (1994). The “grammar” of schooling: Why has it been so hard to change? American Educational Research Journal, 31(3), 453-479.